When people search for “countries with the best doctors,” they are often looking for two things: where they will receive excellent care as patients and where international medical graduates (IMGs) can build strong, sustainable careers. Those answers overlap, but they are not identical.

In reality, “the best doctors” depend on how you define “best”: training standards, patient outcomes, access to care, language, lifestyle, or research opportunities. This guide breaks down those criteria and gives practical context for both patients and IMGs.

What Does “Best Doctors” Actually Mean?

Training and accreditation

In highly regarded systems, doctors typically:

- Complete long, structured training pathways (undergraduate, medical school, residency, and often fellowship).

- Train in accredited programs with defined curricula, minimum case numbers, and continuous assessment.

- Participate in continuing professional development and periodic recertification.

For patients, this usually translates into doctors who are up‑to‑date and comfortable handling complex cases.

For IMGs, look for countries that adhere to the World Federation for Medical Education (WFME) global standards. In “Best” systems, Continuing Professional Development (CPD) is a legal requirement, not a suggestion. For example, UK doctors must “revalidate” every 5 years to prove they are still fit to practice.

Patient outcomes and safety

Another way to define “best” is by looking at survival and complication rates for major conditions (heart disease, strokes, cancer, trauma). The gold standard for measuring this is PROMs (Patient-Reported Outcome Measures). The world’s top hospitals (such as Mayo Clinic and Charité) now weigh PROMs as heavily as clinical data.

The metric is 30-day mortality rates. High-performing systems (like Australia and Norway) maintain significantly lower mortality rates for acute myocardial infarction (heart attack) and stroke compared to global averages.

“Best” also means a “No-Blame” culture. In the US and UK, “Morbidity and Mortality” (M&M) conferences are standard, where errors are analyzed as system failures rather than personal crimes.

Research, Innovation, and Subspecialty Depth

Some systems stand out for the volume of medical research and clinical trials they generate. As of 2025/2026, Germany and the USA lead in active clinical trials for Oncology and Rare Diseases. Australia has emerged as a global leader in “First-in-Human” (Phase I) trials, thanks to an agile regulatory framework.

They also have academic centres that develop guidelines and innovations. These hubs attract complex international referrals and can be especially appealing to IMGs interested in academic or subspecialty careers.

Language, Culture, and Communication

Even in countries with outstanding medicine, patients may struggle if language barriers make it hard to describe symptoms or understand instructions.

Studies show that Cultural Competency training reduces readmission rates. “Best” systems (such as Canada and the US) integrate the “Social Determinants of Health” into their curricula, teaching doctors to understand how a patient’s background affects their recovery.

Key Criteria for Comparing Countries

When you compare countries, it helps to group factors into a few practical categories.

1. Education and Residency Structure

Ask:

- How long is medical school and residency? (Read How Long Does Nursing School Really Take? )

- How competitive is residency entry, especially for foreigners?

- Is training competency‑based, time‑based, or a mix?

- How well are graduates regarded internationally?

2. Licensing Exams and Workload

Strong systems can still feel “bad” on a day‑to‑day basis if the workload is extremely high and staffing is tight. Many attractive destinations have:

- National or regional licensing exams that IMGs must pass.

- Requirements for supervised practice or bridging programs.

- Heavy clinical workloads during residency and early consultant years.

3. Healthcare System Type

Patients may prioritize access and affordability; IMGs often weigh job security, compensation, and working conditions. Consider:

- Public/universal coverage systems (often strong equity and access, but possible wait times).

- Mixed systems (a combination of public and private, more flexibility but more complexity).

- Largely private systems (more choice, can be expensive and inequitable).

4. Work–Life Balance and Compensation

A country can look excellent on paper, but feel unsustainable if burnout is rampant.

Key questions:

- How many hours per week do residents and consultants typically work?

- What is the salary relative to the local cost of living?

- Are there protections against burnout, and how strong are unions or professional bodies?

You can check out Compensation & Work-Life Balance: 5 Countries for Doctors

Countries Often Rated Highly for Patient Care

Lists vary, but several countries consistently rank highly in global rankings for strong healthcare systems, patient outcomes, and medical training.

1. Germany

Germany boasts one of the highest hospital bed densities in the world, approximately 7.8 beds per 1,000 people (nearly triple the US/UK average). Known for the “Bismarck Model,” it offers nearly universal coverage with high autonomy; patients can often book directly with specialists without a GP referral.

Salaries for Assistenzarzt (residents) start at around €60,000–€75,000 and scale significantly with Facharzt (specialist) status. But you must pass the Fachsprachprüfung (FSP)—a grueling medical German language exam—and the Kenntnisprüfung (KP) for license equivalency.

2. United Kingdom

The NHS is one of the world’s largest employers. It is the global leader in Evidence-Based Medicine and clinical trials (e.g., the RECOVERY trial during COVID-19). Patient care is free at the point of use. While wait times for elective surgeries are a pain point, acute and cancer care remains world-class.

For Professionals it offers clear, tiered progression (FY1 to Consultant). A Consultant’s base salary ranges from £99,000 to £131,000, though many supplement this with private practice. The transition from PLAB to the UKMLA (UK Medical Licensing Assessment) and chronic underfunding, leading to “rota gaps.”

3. Canada

Canada consistently ranks highly in Commonwealth Fund reports on patient-provider relationships. It focuses heavily on “Social Determinants of Health.” For patient care, a single-payer system is publicly funded. It excels in chronic disease management and primary care longevity. General practitioners (GPs) are highly valued here, often earning CAD 250,000–350,000.

The Hurdle is the “Catch-22”—most provinces require Canadian PR (Permanent Residency) to even apply for residency (the MCCQE Part I is the standard exam).

4. Australia

Australia spends about 10% of its GDP on healthcare and has a unique “hybrid” system where private insurance is incentivized to take the load off public hospitals.

They have excellent outcomes in skin cancer treatments and emergency medicine. They are known for the best “dollar-to-hour” ratio. Junior doctors often earn $80,000–$120,000 AUD, while senior consultants can exceed $400,000 AUD.

The challenge is the 10-year moratorium (Section 19AB), which often requires IMGs to work in “Districts of Workforce Shortage” (rural areas) for several years.

5. Scandinavian countries (e.g., Sweden, Norway)

Norway spends more per capita on healthcare than almost any nation. These countries prioritize preventative medicine over reactive treatment. They have the world-leading infant mortality rates and post-operative recovery stats. Digital health is seamless; 99% of prescriptions are electronic. For Professionals, 35–37-hour workweeks are the norm. Parental leave is world-leading (up to 480 days in Sweden).

Language is a non-negotiable barrier (C1 level required). Salaries are flat; the gap between a nurse and a surgeon is much smaller than in the US.

6. United States

The US dominates the Nature Index for high-quality research output and holds the majority of the world’s top 10-ranked hospitals (e.g., Mayo Clinic, Cleveland Clinic). It is exceptional for complex pathology (oncology, neurosurgery). If you have the “Gold Plan” insurance, wait times are virtually zero.

For Professionals, the earnings ceiling is the highest. Specialists (Orthopedics/Cardiology) frequently earn $500,000–$800,000+ USD. The USMLE Step exams are widely regarded as the most difficult in the world. High litigation risk (malpractice insurance) and administrative burnout are significant factors.

Best Countries for Medical Residency if You’re an IMG

For an International Medical Graduate, “best” isn’t just about the hospital’s reputation—it’s about the statistical probability of matching and the legal path to staying.

Statistical Probability: The “Match” Reality

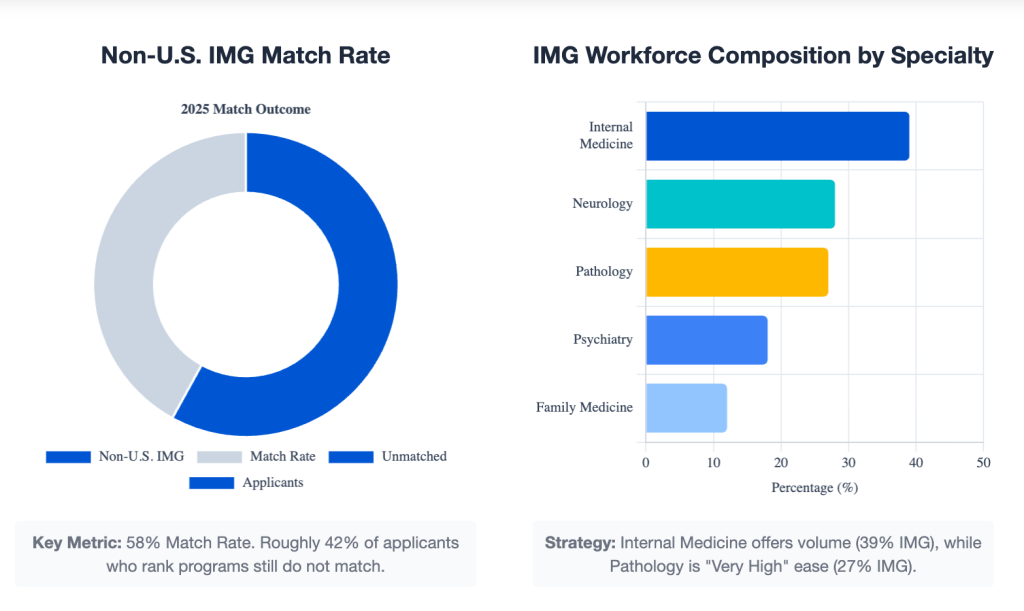

Don’t just look at prestige, look at the fill rates. In the US, the 2025 Match results showed a significant divide:

- Non-U.S. IMG Match Rate: ~58% (highly competitive).

- IMG-Friendly Specialties: Internal Medicine, Pathology (27% IMG), Neurology (28% IMG), and Psychiatry.

- The “Safety” Zone: Family Medicine often has a lower fill rate (~85%), making it the most accessible gateway for IMGs.

Language Requirements and Exams

The “effort-to-entry” ratio varies wildly by country. English‑speaking countries typically require language tests and national licensing exams. Non‑English‑speaking countries usually require high‑level proficiency in the local language plus country‑specific exams.

- USA- Key exam is USMLE Step 1, 2CK, and the Language Requirement is OET (English)

- UK- Key exam is UKMLA (replaces PLAB) and the Language Requirement is IELTS (7.5) / OET

- Germany- Key exam is FSP & Kenntnisprüfung, and the Language Requirement is C1 Medical German

- Australia- Key exam is AMC Parts 1 & 2, and the Language Requirement is IELTS / OET

- Canada- Key exam is MCCQE Part 1 & NAC, and the Language Requirement is IELTS / OET

Recognition & Specialization

Germany’s “Easy” Entry

Germany is widely regarded as the easiest path for IMGs due to a significant physician shortage. Unlike the US “Match” system, you apply directly to hospital departments. If you have the C1 language certificate, you can often secure a residency in a “Tier 1” city like Berlin or Munich.

Spain’s “Equal Footing”

In Spain, you take the MIR exam. Your score is the only thing that matters. If you outscore a local, you get the spot—no subjective interviews or “U.S. clinical experience” required.

The Canadian “PR” Wall

Most Canadian residency spots are reserved for those with Permanent Residency (PR) or Citizenship. Many IMGs immigrate as skilled workers first, get their PR, and then apply for residency.

Visa, Immigration, and Long‑term Prospects

A system that trains you but limits your ability to settle may not be “best” for long‑term planning. A residency spot is useless if your visa expires the day you graduate. Ask:

- Can you realistically stay in the country after training?

- Are there clear pathways to permanent residency or citizenship?

- Are there restrictions on where you can work or how you can practice?

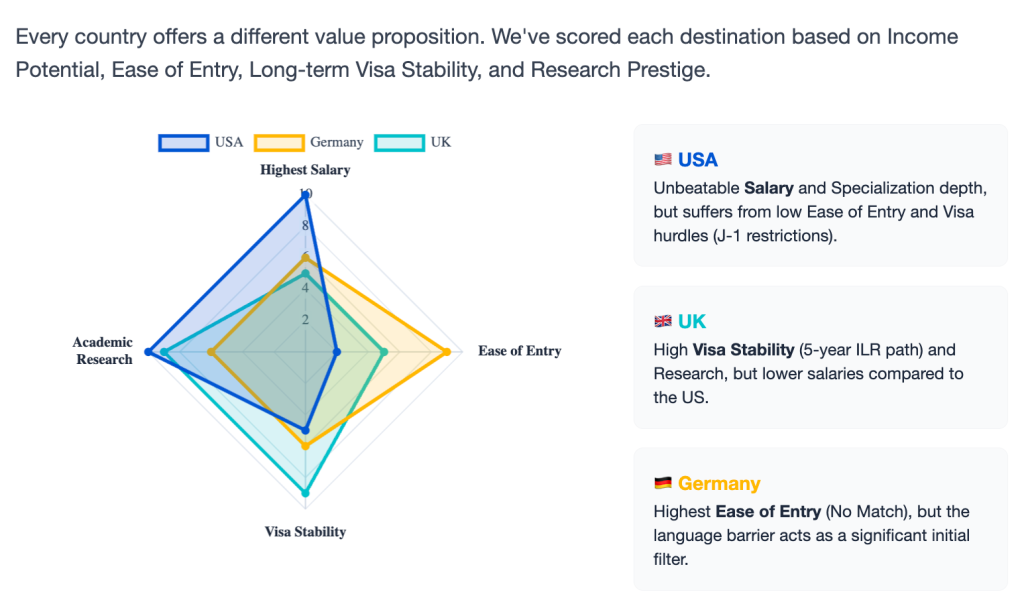

In the US, most IMGs enter on a J-1 visa (requires you to return home for 2 years unless you get a “Waiver” in an underserved area) or an H-1B visa (rare, but allows a path to a Green Card). In the UK, the Health and Care Worker Visa is currently very supportive, offering a direct 5-year path to Indefinite Leave to Remain (ILR).

Australia, on the other hand, often requires a “10-year moratorium,” meaning you must practice in a rural or “priority” area before you can move to a major city like Sydney.

How IMGs Can Choose the Right Country for Training

If you are an IMG, use a simple framework before you commit years of effort:

Clarify your goals

Do you prioritize a specific specialty, income level, academic research, or lifestyle? Are you aiming to settle permanently or train and return home?

- Goal: Highest Salary & Sub-specialization? → Target the USA (USMLE path).

- Goal: Fastest Entry / Direct Hire? → Target Germany (Language path).

- Goal: Best Quality of Life & Family Support? → Target Australia or Scandinavia.

- Goal: Research & Academic Prestige? → Target the UK (NHS/Oxford/Cambridge).

Shortlist 2–3 countries

Check language requirements, exam pathways, and competition levels. Join IMG forums or alumni groups to hear first‑hand experiences.

Map the pathway

List exactly which exams, documents, and supervised periods are required. Estimate time and costs over 3–5 years.

Stress‑test the plan

Ask: “If it takes longer than expected, can I still afford this financially and emotionally?” Have a backup option (in a different country, with a different specialty, or with a different timeline).

No single country is universally “the best” for every IMG. The right choice is the one where the pathway, language, system culture, and long‑term life plan align with your personal priorities.

Next Steps

For patients, the next step is to focus less on country labels and more on finding reputable hospitals, specialists, and multidisciplinary teams that fit their condition and budget. For IMGs, start by listing your top three priorities (specialty, destination, lifestyle), then research 2–3 candidate countries in detail—entry requirements, exam steps, and realistic match chances—before investing heavily in any one path.

Join the Hostalky community on LinkedIn to connect with IMGs already practicing in the US, UK, Germany, and Australia.

Related Articles to Check Out:

QQ88 LÀ NHÀ CÁI CƯỢC UY TÍN SỐ 1 VN